By Dan Wellock

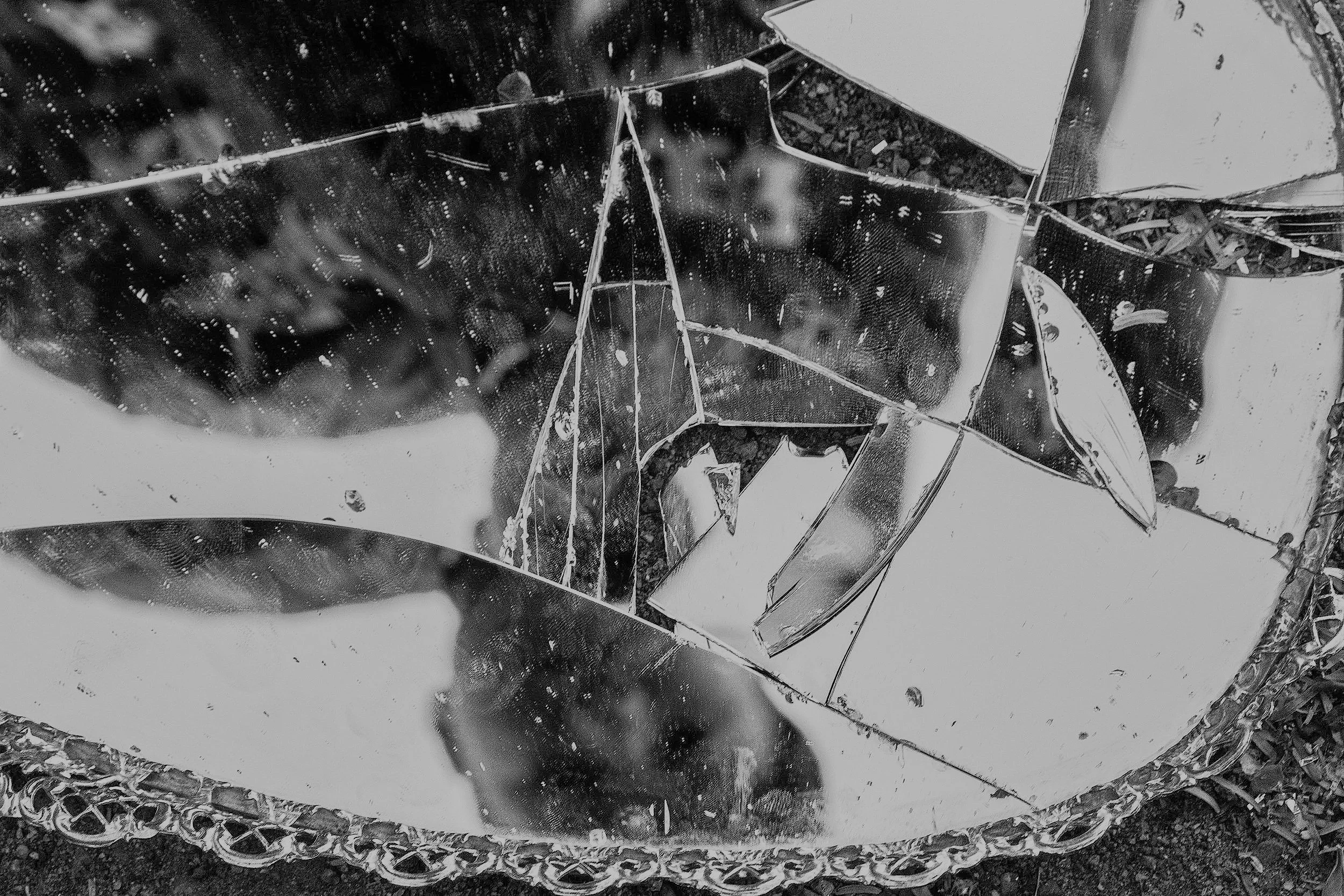

“Don’t run away from grief, o soul,

Look for the remedy inside the pain,

because the rose came from the thorn

and the ruby came from a stone. ”

My phone buzzed on my desk, and I knew the worst had come true.

My older brother had been missing for the past twenty-four hours, and we knew he was not in a favorable mental state. Everyone else in the family was on the road to his home in St. George, Utah to look for him. I was the closest, being in Provo, but I didn't have a car. So, I waited, sitting in fear and trembling, hoping that this was just another one of his solitary trips for introspection.

It wasn't.

My mother's choking voice kept me up for days after his death. I will never forget it. "They found him. He's gone,” she barely got out.

The grief hit me like a train. All I could think to do was don my running shoes and sprint into the night. Even before I started running, I couldn't catch my breath. My whole body shook, and yet a terrifying numbness stole over me. My dear brother—the man who had always been my childhood hero, my idol, and the origin of many interests and hobbies—was dead by his own hand.

In the first week after he passed, I sought to numb the soul-crushing pain that had stolen over me as a night without stars. Even though I don’t usually play videogames, all I did was game and sleep. I drowned my sorrow in ice cream and fantasy worlds. But as his funeral approached, I knew that I needed to feel the grief. Otherwise, I would be an emotionless zombie, unable to show my brother the respect he deserved.

So, I went back to the practice that had helped me through OCD: mindfulness. I began meditating two times a day. I was present in everything I did. The pain came, just as I expected, and it came hard. But when his funeral arrived, I gave him the farewell I knew he deserved. In the four months since then, I have continued mindfulness, and I have found peace in the practice.

In the course of three articles, I am going to look at the research behind the intersection between mindfulness and grief. This is a relatively sparse field academically, but some researchers have looked into how mindfulness-based practices can help the grieving. In this article, I am briefly going to lay out what psychologists and philosophers have written about the experience of grief, though I will not be able to give a full account. This is very important because, in the mad dash for statistics and measurements, researchers often neglect the qualitative lived experience of mental phenomena. In order to find out how to treat grief, it is important to know what grief is and what it feels like.

First, we should define grief as it is given in much of the literature. For the purposes of this article, I am going to assume that grief pertains to the loss of a loved one rather than other kinds of loss, which have been shown to cause grief (Janske et al., 2022). We are taking this approach because non-death losses are likely a different kind of experience than loss of loved ones.

In the classic literature on grief, researchers make distinctions between bereavement, grief and mourning. According to Dubose (1997), bereavement is understood to be the experience of something or someone being suddenly ripped from one’s lifeworld. This is an immediate severance between the individual and the loss. Dubose also defined grief as “the emotional response to bereavement”. Additionally, he identified mourning as the process of incorporating the loss. These definitions are important so that we know what we are studying. In the case of these articles, we will retain the definition of grief and see mindfulness as an action of mourning. We will also incorporate bereavement as part of grief, so the terms will be used interchangeably.

Much of the literature surrounding the phenomenon of grief identifies that a loss of identity is almost always a part of the experience of grief. Køster (2025) theorizes that there are four types of existential loss in grief: habitual, practical, historical, and narrative. Understandably, losing any element of one’s identity is distressing, much less losing four core aspects.

The first type of identity loss Køster (2025) describes is habitual identity. This is the experience that we have of continually being brought back to a familiar environment and creating habitual practices (Køster 2025). This is an essential element of maintaining a sense of self because much of what we do is habitual, and it often includes our cherished relationships. When a relationship is severed suddenly, we lose the habitual identifier of associating with the individual. Whereas conversations happened often, now the inside jokes, agreements, and disagreements are seemingly gone, and we are left bereft of a grounding part of the self. When we call, there is no one on the other line. When we visit, the house is vacant. When we meet with family for holidays, a chair is empty.

The second type of identity loss discussed by Koster is practical identity. Our practical identity is established through values and commitments (Køster 2025). In a Jamesian pragmatic sense, we build our practical identity so that our values and commitments guide our lives. When we are presented with a novel situation, we fall back on our convictions and our desired attributes so a choice can be made. When we lose a loved one, we not only lose the person, but also the commitments, values, and roles associated with them. And if convictions still stand, they are often shaken by the absence. A belief held strongly can falter quickly in the face of bereavement. This is vividly reflected in A Grief Observed, an account on grief by theologian C.S. Lewis. Though deeply religious, he pulls no punches when he writes, “Meanwhile, where is God? …. Go to Him when your need is desperate, when all other help is vain, and what do you find? A door slammed in your face, and a sound of decreeing and double-locking on the inside. After that, silence." We never know how much our values are based on another until they are gone.

The third identity loss is the loss of our historical identity. This is the foundational aspect of our identity based in a shared historical horizon that stretches from the present into both the past and the future (Køster 2025). When we lose a loved one, we notice sharply how foundational aspects of the self built from memories with the individual are suddenly taken away. Locations, books, movies, and opinions reach out for their origin, but it is gone.

Finally, the last form of identity loss is our narrative identity. The self is mostly constructed in a narrative framework (Dunlop and Walker 2013). Indeed, when we lose someone dear, our future story is bereft of a major figure—one who played a part in forming the self. There is a hint of the person as we engage in activities they loved, hear songs to which they introduced us, or go to locations we went to together. However, they do not figure in the story as they did before, and we reach out grasping for the phantom trace of a memory.

Now on to the feelings associated with grief and these losses of identity. Fuchs (2017) described the bodily experience of grief as, “bodily heaviness, passivity, constriction and withdrawal.” We feel a traumatic blow when we hear the news, often saying things such as “that cannot be true!” Then grief sets in, making us feel a kind of weight, a pressure on the chest, and a choking with grief. Additionally, there is a kind of palpable darkness that overshadows life. While noting some of the similarities with depression, Fuchs (2017) shows that grief does not usually come with the bodily rigidity and loss of emotion characteristic of depression. Depression usually manifests with a frozen mood, while grief generally appears as pangs of pain. In keeping with the bodily description, grief becomes akin to an amputation.

“You care so much you feel as though you will bleed to death with the pain of it.”

The loss extends from the body into the very cognition of the survivor. Grief generally includes a confusion between presence and absence. The literature calls this phenomenon “ambiguous presence”, and it arises because the survivor perceives the dead body (or, when the body is not found, the idea of the body), so there is a physical manifestation of the person, yet the person as experienced throughout life is gone (Fuchs 2017). This is the root conflict in grief, and acceptance, generally considered the last “stage” of grief, includes resolving the question of whether the deceased is here or away. We can understand why acceptance requires a lot of time.

There is not enough space here to give a full phenomenology of grief. That would likely be book-length and require much more qualitative research. However, the loss of identity is a primary experience in grief, and mindfulness practices help ground the individual through the identity change. Bodily pains and reactions are normal and natural, and mindfulness can help us not only endure them, but embrace them with self-compassion. Finally, the ambiguous presence can be resolved through mindfulness practice because acceptance of the present moment can be practiced and inculcated. In the next article in the series, we will look at what the research says about mindfulness treatments for grief.

References

DuBose, J. T. (1997). The Phenomenology of Bereavement, Grief, and Mourning. Journal of Religion & Health, 36(4), 367. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1027489327202

Dunlop, W. L., & Walker, L. J. (2013). The life story: Its development and relation to narration and personal identity: Its development and relation to narration and personal identity. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 37(3), 235-247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025413479475

Fuchs, T. (2018). Presence in absence. the ambiguous phenomenology of grief. Phenomenology & the Cognitive Sciences, 17(1), 43–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-017-9506-2

Køster, A. (2025). Understanding loss: an existential framework. Philosophical Psychology, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515089.2025.2457479

Van Eersel, J. H. W., Taris, T. W., & Boelen, P. A. (2022). Job loss-related complicated grief symptoms: A cognitive-behavioral framework. Frontiers in psychiatry, 13, 933995. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.933995