What is Flow?

““My mind isn’t wandering. I am not thinking of something else. I am totally involved in what I am doing. My body feels good. I don’t seem to hear anything. The world seems to be cut off from me. I am less aware of myself and my problems.”

The psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi began studying the optimal experience of sailors, artists, and musicians in the 1970’s. He asked them about what they felt like when they were having peak experiences, what led to those experiences, and what stopped those experiences from happening. He used the term flow (a term that these people frequently used when discussing the topic) to describe their peak experiences. These people described times when they felt like they were immersed in their activities, and they were operating at their peak level of performance. Csikszentmihalyi found that two basic factors (high challenge level and high skill level) were related to whether people experienced flow.

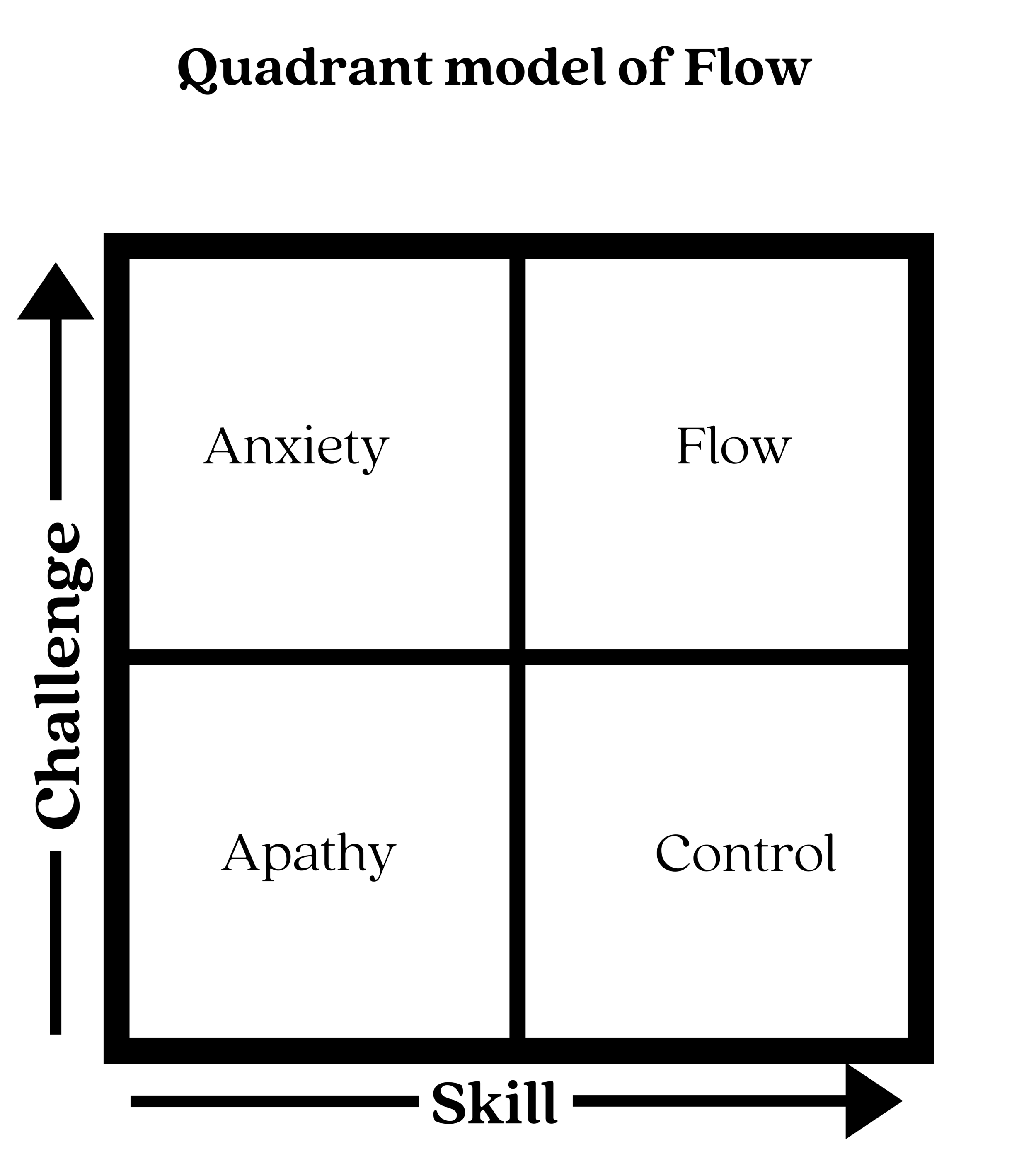

Csikszentmihalyi and subsequent flow researchers have used experience sampling to study flow. In these studies, research participants are given a device that will go off at random times during the day. When the device goes off, they take a survey asking how they were feeling when the device went off, and what activity they were participating in. Because they take surveys at random times (possibly at breakfast, during work, or while they’re waiting for the bus) they record information about a variety of experiences. Early researchers confirmed Csikszentmihalyi’s theory that flow experiences generally happened when somebody was engaged in an activity that was challenging, and in which the person is exercising high amounts of skill. This model of flow is sometimes the quadrant model, and it is shown below.

Subsequent researchers have built on this quadrant model and concluded that more kinds of experiences should be used to describe combinations of skill and challenge. They found that people’s experiences don’t fit neatly in these four categories, and that not all “optimal experiences” happened with the same balance of challenge and skill. In this new experience fluctuation model, experience level and challenge levels combine to create states of apathy, worry, anxiety, arousal, flow, control, relaxation, and boredom. Though the model became more complex, the main idea remained: flow experiences happen when high levels of skill meet high levels of challenge.

Flow experiences have been characterized by the amount of deliberate and automatic thinking they employ. Deliberate thinking processes are those in which the mind slowly comes to conclusions based on rational thought. In these processes you are conscious of all the reasoning behind a conclusion or a decision. Automatic processes are those in which the mind comes to a conclusion without your conscious awareness. The mind strengthens its automatic processes as it does an activity frequently, and these processes can be developed for many different kinds of activities.

Flow has been compared to intuition because both categories of experience show a similar relationship between deliberate and automatic thinking processes. Both flow experiences and intuition involve minimal amounts of deliberate thinking, and high amounts of automatic processing. The conscious mind (which is relatively slower) doesn’t need to act in either state, so decisions and tasks can be done quickly and accurately. People experience a thrill at being able to accomplish tasks without needing to consciously think about them, and they enjoy the lack of concern and worry that comes when automatic processes take over. However, this enjoyment comes at a cost—lots of practice is necessary for the neural connections involved in an activity to become automatic.

Flow as a universal experience

Flow is a universal human phenomenon—occurring across cultures, activities, and social status—that plays an integral part in work, education, social life, and recreation. Some activities have been created to produce flow. For example, when designing video games, game architects ensure that those who play the games are able to play the games at their optimal level of skill and challenge by giving players many options of challenge levels and allowing players to choose which challenge level best suits them. Flow happens in education as people learn new things. Music is particularly conducive to flow experience, as there are nearly limitless options for increasing challenge if a musician desires. As you can tell from these many examples, flow happens in the everyday lives of ordinary people—not just in the lives of professionals at the top of their field.