By Andrea Hunsaker

“Stay with it. The wound is the place where the Light enters you.”

I have a memory from my teen years of listening to my younger sisters playing in the next room. By the sound of it, it was an intense game of make believe. The melodrama was abruptly interrupted when my six-year-old sister broke character and let out a frustrated groan, “Ugh, I hate my pee!” I heard a quick succession of feet run to the bathroom, the flip of the toilet seat, a stream, a run back to the dolls, and a seamless reentry to the fantasy world as if she had never left.

(Only now am I realizing there was no sound of a bathroom door closing—or hand washing—but anyway.)

This memory of mine pops up at the oddest moment. I’m sitting across from a client in the counseling room who is describing a painful relationship experience. Her mind is working hard to analyze and understand—essentially trying to fix it in her head so she doesn’t have to feel it in her body. I’ve invited her to take a moment and drop down into her body and notice where the feelings are felt. At first, she struggles to pinpoint it. This can be a big ask especially when the emotions are inconvenient or deeply unpleasant. Why turn toward something I don’t want? Often, people have trouble with this. I get answers like, “I don’t know”, “All over“, or “In my head”. Our habits of distracting, numbing, and avoiding the felt sense of emotional discomfort can cut us off from the body, leaving us emotionally constipated—disembodied heads playing out the stories our minds create, not unlike my sister’s melodrama. After a minute of attention inward, my client finds a knot in her chest, heavy and hard. As she stays with it—allowing it to be as it is, bringing curiosity and tenderness to it—I ask her what this knot needs. She tears up. It needs to be seen. It needs to be felt.

What’s so different about recognizing the felt sense of a full bladder and attending to what it needs than recognizing the felt sense of an emotion and attending to that?

The Inside Sense

This skill is called interoceptive awareness: the ability to sense internal signals like heartbeat, breath, muscle tension, hunger—and the bodily cues of emotion, like a tight chest or butterflies in the stomach. This means learning to notice and accurately interpret what your body is telling you—then using that information to care for yourself. Studies show dysfunctions in interoception are linked to anxiety, depression, eating disorders, PTSD, and substance abuse (Khalsa et al., 2018). In contrast, people with high interoceptive awareness can more effectively downregulate negative emotions and better handle social uncertainty (Pinna et al., 2020). You have to feel it to heal it. The good news: your inside sense can be trained.

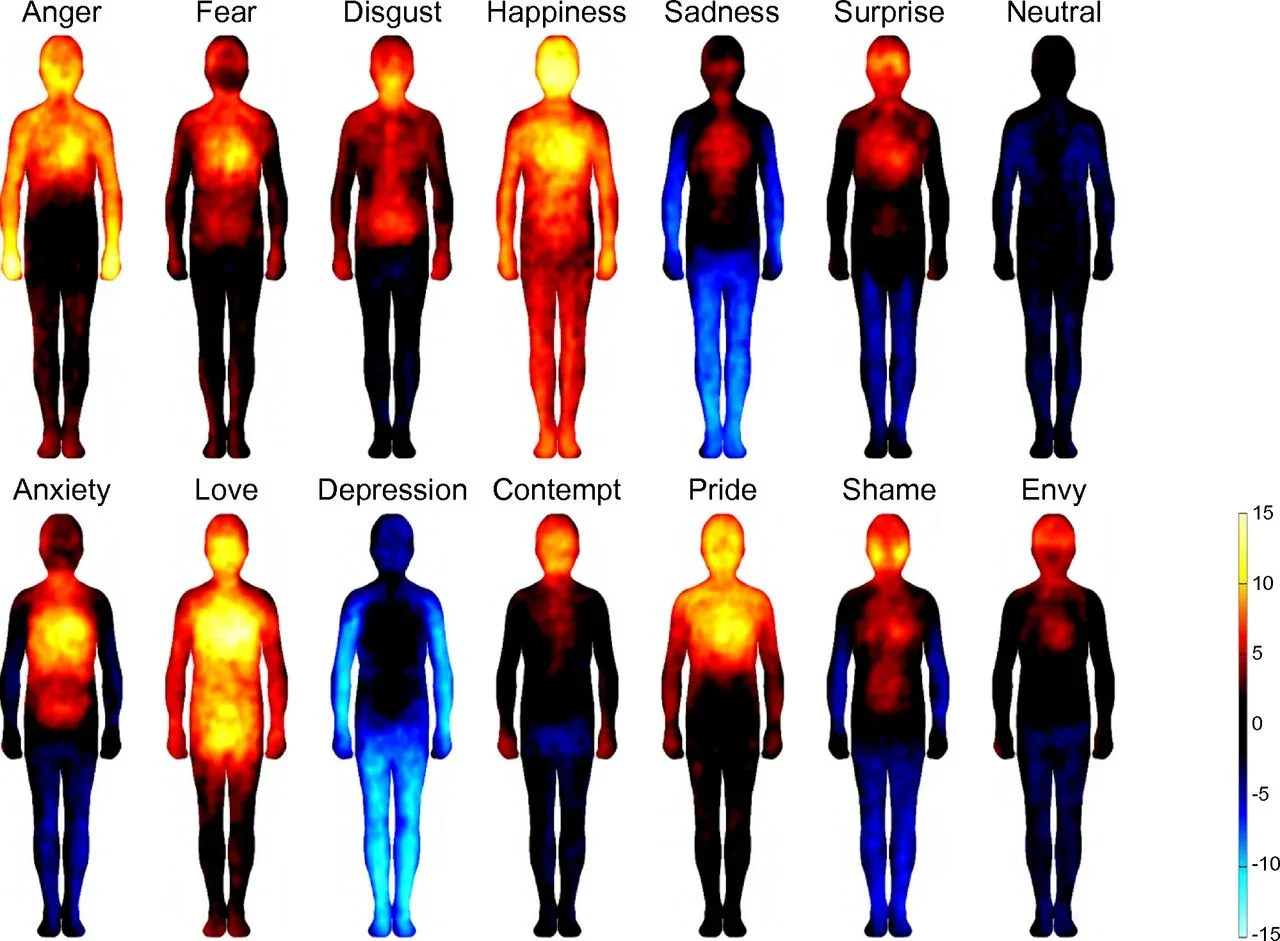

The figure below (Nummenmaa et al., 2014) maps where 701 participants from Europe and Asia felt common emotions. The warm colors represent activation while the blues represent deactivation in those areas. It’s evidence that across cultures, emotion sensation patterns in the body are highly universal. (And possibly that Spiderman feels shame.)

(Nummenmaa et al., 2014)

How to Increase Interoceptive Awareness

I recently tried a sensory-deprivation tank. For an hour I floated in a black, soundless saltwater pod with nothing to do but listen to Darth Vader—who turned out to be my own breathing, amplified by 100. Without the distraction of the usual sensory circus of everyday life, I could be with my own body. It felt like a homecoming: serenely grounded in the rhythm of my heart while floating in space. For me, it was direct experience that my body was a safe place, emotions and all. Research on these flotation-REST tanks show benefits for stress, mental well-being, clinical anxiety, and chronic pain (Lashgari et al., 2025). In one study with anxious participants, a single float session increased interoceptive awareness and deep relaxation—suggesting the low-stimulation environment helps people attend to breath, heartbeat, and internal signals more clearly (Feinstein et al., 2018). But in case you don’t have unlimited funds for regular float tank sessions, here are a few other ways to increase interoception:

Name & Normalize. Put simple words to emotions and sensations: “joy—warmth in chest,” “anxiety—tight throat,” “disgust—hollow belly.” Notice pleasant and difficult sensations. Then add a welcome: “It’s okay that this is here.”

60-Second Body Check. Throughout the day, pause and scan head-to-toe. Ask: What sensations are here? Where? What’s the intensity (0–10)? No need to fix—just notice.

Exhale-Lengthening Breath. Inhale naturally; lengthen the exhale by a few seconds. Longer exhalations calm the nervous system.

Emotion Map. When you notice an emotion, note three layers:

Body: “heart racing, heat in cheeks”

Feeling: “anxious + embarrassed”

Need/Value-aligned action: “step outside, 3 slow breaths, then clarify expectations”

Interoceptive Journal. One sentence a day: “Today my body said ____, I responded by ____, result was ____.” This builds pattern awareness.

Gentle Exposure. If some sensations attached to emotions feel scary or painful (e.g., a racing heart, heavy chest), approach in small doses—notice for five seconds, then return to the breath. Expand gradually.

Feel What’s Real. Heal

Emotional intelligence begins in the body. When you notice subtle shifts—faster breathing, clenched jaw, fluttering stomach—you can understand and label your experience more accurately (nervous, not unsafe) and regulate more quickly. You can heal patterns of numbing or overriding emotional signals by gently turning toward them instead of avoiding them. And you are more sensitive to the positive emotions your body experiences. Your body isn’t a problem, and emotional sensations aren’t inconveniences; they are vital information. By learning to feel what’s real—instead of living solely in the mind’s melodrama—you can meet your needs sooner, heal, and move toward the life you want.

“What is split off, not felt, remains the same. When it is felt, it changes.”

References

Feinstein, J. S., Khalsa, S. S., Yeh, H., Al Zoubi, O., Arevian, A. C., Wohlrab, C., Pantino, M. K., Cartmell, L. J., Simmons, W. K., Stein, M. B., & Paulus, M. P. (2018). The Elicitation of Relaxation and Interoceptive Awareness Using Floatation Therapy in Individuals With High Anxiety Sensitivity. Biological psychiatry. Cognitive neuroscience and neuroimaging, 3(6), 555–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2018.02.005

Khalsa, S. S., Adolphs, R., Cameron, O. G., Critchley, H. D., Davenport, P. W., Feinstein, J. S., … Paulus, M. P. (2018). Interoception and mental health: A roadmap. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 3(6), 501–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.12.004

Lashgari, E., Chen, E., Gregory, J., & Maoz, U. (2025). A systematic review of flotation-restricted environmental stimulation therapy (REST). BMC complementary medicine and therapies, 25(1), 230. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-025-04973-0

Nummenmaa, L., Glerean, E., Hari, R., & Hietanen, J. K. (2014). Bodily maps of emotions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(2), 646–651.

Pinna, T., Edwards, D. J., Colautti, L., Meneghetti, C., & Gobbetto, V. (2020). A systematic review of associations between interoception, vagal tone, and emotional regulation: Potential applications for mental health, wellbeing, psychological flexibility, and chronic conditions. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1792. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01792

Stein, M. B., Stephan, K. E., … Interoception Summit 2016 participants (2018). Interoception and Mental Health: A Roadmap. Biological psychiatry. Cognitive neuroscience and neuroimaging, 3(6), 501–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.12.004